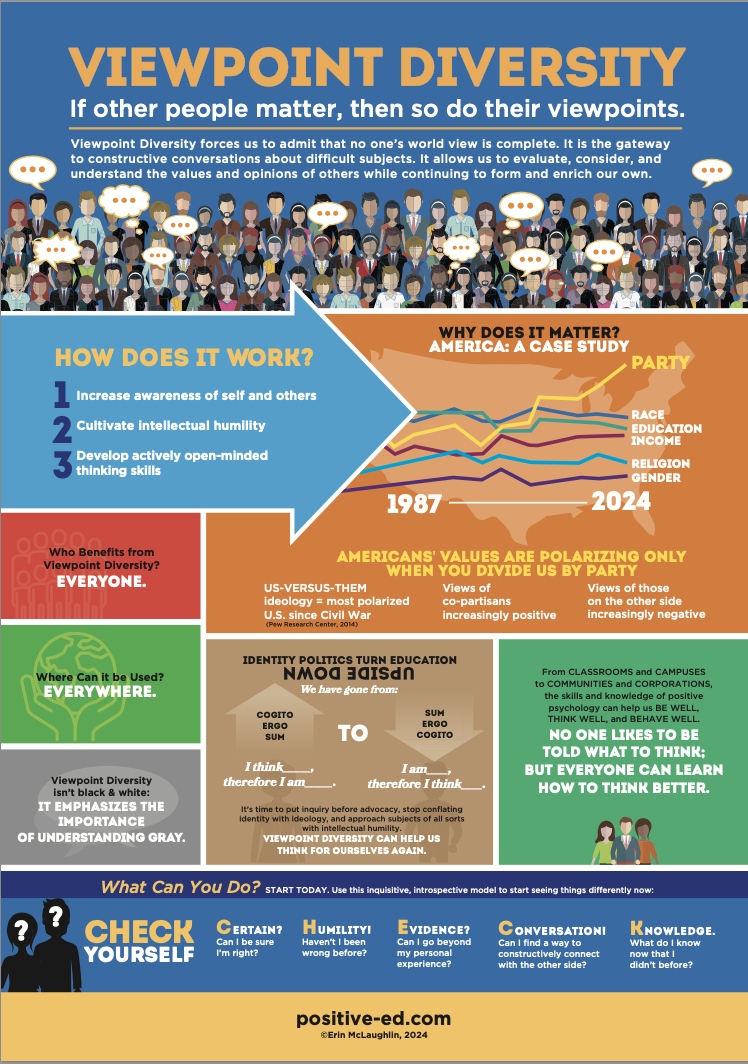

This poster serves as a colorful reminder of the importance of viewpoint diversity and offers a key to practicing it in your own space. On sale now for $25, it can be resized to any dimensions.

Viewpoint Diversity Gains Traction! Interview with Erin McLaughlin Published in The Atlantic

Recently, Erin McLaughlin, founder of Positive-Ed Consulting, was interviewed by Conor Friedersdorf of The Atlantic about her ideas regarding Viewpoint Diversity. More than just an educational curriculum, McLaughlin believes it has all the potential to change a culture. Read the full article here!

Yes, You Can Have It All (One Moment at a Time)

by Abigail Somma

There it was again – that question – the question that comes up every so often around the topic of women walking the tightrope between professional and family life: can women have it all?

This time the question came up at a meeting hosted by the Obama Foundation in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and was directed toward former first lady Michelle Obama and actress Julia Roberts.

The women seemed to be in agreement that having it all was “a headline,” “a myth” and “stupid.”

“You have to define your terms of what “all” means. All is different for everyone,” said Roberts.

“I’m not supposed to have it all,” said Obama.

The premise of “having it all” has been around for a long time. It perhaps first entered into popular culture in 1986, when former Cosmopolitan editor Helen Gurley Brown penned the book Having It All: Love, Success, Sex, Money Even If You're Starting With Nothing. The notion that women can balance both a fulfilling home life and a thriving career - ie, have it all - has been enticing women ever since with a carrot that feels just out of reach.

In 2012, "having it all" - or not - hit the headlines when lawyer and professor Anne-Marie Slaughter wrote an article for the Atlantic Monthly titled: Why Women Still Can’t Have It All. In her piece, Slaughter makes a compelling case that for women in her demographic, having it all – as in holding a hyper-demanding leadership position while maintaining a degree of presence for children – is simply not possible. She points out that having it all comes with a high price many women just aren’t willing to pay. “In short, the minute I found myself in a job that is typical for the vast majority of working women (and men), working long hours on someone else’s schedule, I could no longer be both the parent and the professional I wanted to be—at least not with a child experiencing a rocky adolescence,” she wrote.

Along with suggesting an array of social changes, Slaughter ultimately recommends women anticipate a more flexible career arc, and defer on the most demanding positions until children are out of the house. She references a common turn of phrase many senior women pass on to their protégés: “you can have it all; you just can’t have it all at once,” but she offers caution about the interpretation. It’s not so much about figuring out the perfect time to have children as it is about having patience and adopting a long-term view.

Indeed, asking women if they can find personal balance in an imbalanced society and working culture does feel like a false start. It's something I know well from personal experience. After spending a year and a half at home with my children, and amassing debt to do so, I decided to go back to work full-time and quickly found myself unable to attend to the rigors of NYC city’s work culture and feel like a genuine presence for my twin toddlers. Two months later, I dropped out of the full-time workforce in a moment that was heavily mixed with both defeat and relief.

Over the next few years, I voluntarily spent much of my time with my small children and there were plenty of times when I certainly didn’t feel like I had it all. But at the same time, I also began to see the question in different terms. Partly due to a career shift toward training companies in mindfulness meditation, my perspective shifted: even though I didn’t have it all on paper, there were some moments when it felt like I did have it all and some when it felt like I didn’t. In that sense, having it all was a moment-by-moment experience. Different than the not-all-at-once interpretation, I would say, yes, we can have it all, but only sometimes and only if we awaken to it.

The question of having it all has long been posed in the macro-form where having it all means maintaining a high-powered, successful career while raising well-adjusted, healthy children. But in the micro-form, the question looks a little different, as in: do I have everything I need – just in this moment – to be happy? And sometimes the answer is simply: yes, I do. From the moment-by-moment perspective, we might very well have a lot more having it all moments than we realize.

In my life with two five year olds, sometimes I’m happily sandwiched between their squirmy bodies and there it is. I have it all. About a half hour later they’re fighting like the idiomatic cat and dog and I want to scream out, “Calgon, take me away!!!” (because I’m a child of the 1980s after all). In those moments, I definitely don’t have it all. But just a little while earlier, I did. When I’m connecting with a participant at a workshop, and in the back of my mind, I know my children are in loving care, I have it all. But then later, I’ll lament that I’m not further along in my career, and I don’t. From the moment-by-moment perspective, having it all ebbs and flows, like pretty much everything else in life. Part of the good life is simply recognizing and waking up to those fleeting moments when indeed we do have it all, and doing whatever we can to maximize them, including developing patience for the moments when we clearly do not have it all (surely, you know those moments.)

In macro-terms, having it all is solely a women's question because society has rendered it so much harder for women to have a successful career and raise children. But at the micro-level, having it all is everyone’s question. There are plenty of men working ten hour days, who only see their kids on weekends, and they hardly feel like they have it all. They may be working long hours to make ends meet, not because they’re passionate about the job. They may feel pressured, short on time or overwhelmed. For both women and men, stress is the number one enemy of having it all.

Furthermore, the traditional parameters of having it all, focused on children and career, don't feel relevant for many people or apply to their lives. But in micro-terms, anyone can have it all in any moment that we notice the good and allow feelings of contentment to arise. Sitting with a pet, sipping tea, or even doing the dishes, can all be moments to look around and say, in this moment, I have it all.

While a large part of having it all is a genderless moment-by-moment experience, that doesn’t mean we stop trying to create change at the macro-level or let our governments and employers off the hook. When my children were two years old, I didn’t just step back from working full-time. Due to hyper-expensive childcare and overwhelming working hours, our family left New York City all-together and moved to Vienna, Austria, a city with ample parental leave, free early childhood care, and a much more moderate working culture. While managing toddler twins in a foreign country wasn’t always a joyride, being in a society with a sustainable work-life balance made it much easier to find more having it all moments. Balance begets balance.

Social policies notwithstanding, most of us do have moments of quiet (or loud) joy with our children, engaging meaningfully at work or just simply waking up to the goodness already in our midst. We could have more having it all moments than we even realize. As we continue to advocate for the professional and social policies that will make our lives more manageable and enjoyable, let’s not overlook the micro-moments of having it all inherent in nearly every life, every day.

Was the First Thanksgiving the Last One Where Everyone Got Along?

you can shift the conversation to something constructive.

by Erin McLaughlin

Thanksgiving Day is upon us, and with it comes a mix of joy and terror for many, as we anticipate the gathering of family. Family may mean those with whom we share DNA or parents (but sometimes that’s it); old friends, with whom we share common experiences (but sometimes different politics); and in-laws, with whom we share a love for the same people (but sometimes it’s overshadowed by viewpoints that divide us). Much has been written about how to survive Thanksgiving dinner without inflaming warring parties--a rather interesting irony of a holiday meant to illustrate the ability of people to come together and be grateful. While much of the advice out there is sensible, some of it is more amusing than practical, and most of it is difficult to apply in the heat of the moment.

For instance, Marlene Coroselli, author of The Language of Leadership, suggests that hosts should warn guests ahead of time that the word “Kwanza” will be shouted anytime an argument arises. While it’s plausible that this tactic may work in some families, it certainly doesn’t seem like a solution that would work for many. Another more reasonable tip from psychotherapist Sarah Mandel is to bartend responsibly, citing the reality that for many, alcohol causes trouble as we lose our ability to judge what we should and should not say aloud. But this negates the fact that free-flowing libations on Thanksgiving may be a tradition revered by many, and monitoring refills isn’t easy when it comes to our own glasses, let alone the glasses of others.

It’s difficult to hold other people we love accountable, and it certainly can cause added discomfort. Perhaps then we can look to the words of wisdom from William Fitzgerald, an associate English professor at Rutgers University. He suggested last year that we remember why we’re at Thanksgiving dinner in the first place, and to look for common ground instead of engaging in an argument. Fitzgerald says we should resist snark and avoid speechmaking--all good advice but, of course, it also pre-supposes that we are there to connect positively with others and that we have some modicum of self-awareness and intellectual humility.

Even those who are earnestly approaching Thanksgiving with good will may find themselves growing suddenly and viscerally upset when Uncle Bill or Cousin Jenny introduces difficult topics that lend themselves to controversy and deeply held beliefs. If left unchecked, these subjects can veer off the path of civil discourse quickly. Before we can possibly remember our purpose, our positivity, and our poise, we may find our pulses quicken and our righteousness ratchets up. This is often because of two things--pace and space. The very nature of gatherings of people who have diverse viewpoints, where everyone has an equal opportunity to speak and be heard, means that conversations can quickly shift unexpectedly and opinions are often voiced as facts. When faced with an idea spewed across a table that seems so unabashedly wrong, many people don’t have the space needed to choose a constructive path to continue the conversation in a civil manner.

It’s a nice hope, but not altogether reasonable, to expect others to hold themselves in check regarding broaching highly controversial topics during Thanksgiving dinner. And it’s definitely unreasonable to expect everyone to agree. However, for those readers who hope to be part of a more peaceful Thanksgiving this year, there is a strategy for recognizing and respecting one of the most important, least acknowledged kinds of diversity out there--viewpoint diversity. Regardless of race, gender, religion, education, ethnicity, economic status, sexuality, or any other arbitrary identity marker, everyone has a unique viewpoint. And if we believe that other people matter, then their views must matter, too -- even if we happen to vehemently disagree with them.

Viewpoint diversity isn’t about agreement, or consensus, or tolerance. It’s simply about making an attempt to understand a point of view that’s different. This doesn’t mean, of course, that all viewpoints are equal. Some things are indisputable facts, and some opinions may be reprehensible and intolerable. But more often than not, there is some common ground between and among people. Usually, it’s in the form of values; we simply differ in how we prioritize what we care about. The path forward to understanding is one that ultimately makes people better versions of themselves. And there’s an easy way to get started…

This Thanksgiving, the most important thing to do is to keep yourself in CHECK:

Certainty? If you feel yourself feeling certain that someone is wrong and you’re right, ask...

Have I been wrong before? Of course, so then, before we speak, we should think about...

Evidence beyond experience. Seek to make this less personal and more factual, creating...

Constructive conversation. Ask questions, aim for understanding, because that will add to:

Knowledge. Understanding a point of view that isn’t yours makes you a better person.

By taking the time to put things in perspective, by recognizing that not all perspectives are the same and no one’s worldview is complete, CHECK is a system that creates space in a conversation--and within that space is a powerful choice about how to conduct the kind of conversation many of us have been missing in both our private and public spheres. If positive change in our level of discourse is something that we truly desire, then we must take it upon ourselves to start the process. Share this with friends and family. And, those who choose to make the effort can hold themselves accountable by keeping themselves in CHECK. Together, we can make Thanksgiving happy again!

For more information on viewpoint diversity and to find out how to bring viewpoint diversity training to your corporation, business or team, visit https://positive-ed.com/viewpoint today.

The Cost of Connection: Why Businesses Should Care about Loneliness

I sat in the chemistry lecture hall, soaking up the energetic atmosphere that comes with hundreds of people gathered to learn more about positive psychology. It was the annual Summit for those associated with the University of Pennsylvania’s Master of Applied Positive Psychology program, and though the topic was science of a different sort, chemistry was indeed in the air. There was so much talk of love in the room, so many standing ovations that they practically ceased to mean anything at all, that it sometimes distracted from the importance of the information itself. Dr. Vivek Murthy, former US Surgeon General, sat discussing his upcoming book on what he calls “the loneliness epidemic.” And as he spoke, I tilted my head ever so slightly toward a friend and former classmate, and without much thought, said it: “I think I’m lonely.”

“Me, too,” he said.

Murthy served as Surgeon General from 2014-2017. After embarking on an initial listening tour throughout the United States, he decided to focus his platform on what he heard. And what he heard most resoundingly, from people across all demographics, was that people are lonely--and their loneliness is affecting their health. It didn’t take him long to determine that the number of people affected, in all walks of life, qualifies loneliness as an epidemic--a public health crisis that needs to be addressed meaningfully.

It’s no surprise to anyone reading this, I’m sure, that despite the fact that we live in the most technologically connected age that ever was, loneliness in almost all domains of life is practically palpable. I could say measurable rates of loneliness are increasing, and you might argue that we are measuring things we didn’t before--so I will leave it here: loneliness is certainly nothing new. It’s surely part of the human condition--anyone who reads knows this, and C.S. Lewis said that perhaps this is why we read--”to know we’re not alone.” But while technology allows us to connect more easily, there is something superficial, artificial, that cannot replace our need for human interaction. And what do humans spend the majority of their time doing? Working. So interactions at work matter--and employers should be paying attention to this concept.

The magnitude and impact of loneliness has yet to be fully realized or acted upon by most employers. Murthy explained that several factors play into this epidemic: geographic mobility, the increased use of technology, and the nature of work itself. More and more people move away from close family and friends to pursue careers; fewer meaningful connections are made at work, where often an email replaces a conversation; and work itself cuts into precious time once reserved for connecting with family and friends. We are perhaps all at a point where we should be saying: “I know it’s easier to send a text, but is it better?”

Murthy cited some numbers that surprised me, but the one that stuck with me is that loneliness or weak social connections are associated with a reduced lifespan that is about the same as smoking 15 cigarettes a day. As someone who lost her smoker-dad to lung cancer when I was 21 (and he was 57), that one hit me hard. Loneliness also puts people at greater risk for cardiovascular disease, dementia, anxiety, and depression.

What does this mean for employers, and how can you help?

If your employees are lonely, it will decrease their performance, limit their ability to be creative, and generally impair other domains of their executive function, such as being able to reason or make good decisions. Murthy explained that a good start for businesses is to actually assess the state of connections in the workplace--do employees feel genuinely valued? Is there a culture that supports helping each other? Is there an opportunity to be seen as a whole person--as more than just the role one is performing?

The best workplace cultures are supported by strategic planning that promotes meaningful connections. This means fostering a corporate culture where it is expected and encouraged that colleagues will freely give and receive help, where people are meant to be wholly understood and are given the opportunity to connect with others as much as possible, and where time outside of work has measures of protection so that employees at every level have time off with family and friends to cultivate connections that are intimate and invaluable.

Each of us, regardless of our role at work, has a fundamental human need for connection. If we aren’t proactive in making time for meaningful connections that are positive, my fear is that we will settle for connections that are potentially toxic to our well-being. Because it simply feels better to connect in the wrong way, rather than not to connect at all, many of us engage in unhealthy relationships that we reason at least give us something, rather than nothing. This can manifest in all kinds of behaviors, including partaking in tribalism that can be easily seen in the overt polarization that’s happening globally, or engaging in unhealthy personal relationships that are comfortable but are not in any way making us better.

We all have the potential to be better versions of ourselves. The most progessive workplaces will want to see that happen. Not just because there’s an ROI for employees who are more positive and engaged, but because it actually makes the world a better place to be for all of us.

Viewpoint Diversity: What it is and why it matters

In today’s climate of intense polarization, people on all points of the political spectrum have strongly advocated for their personal beliefs and many aren’t afraid to be confrontational with friends, family, or strangers on “the other side.” You’ve probably seen these arguments play out over social media – or maybe even at the dinner table. In this age of identity politics, viewpoint diversity has become essential to foster personal intellectual growth, and it’s clear that the earlier this process begins, the better. The key is to promote individual thinking over group-think, celebrating unique points of view and recognizing that other people’s points of view matter, too.

Viewpoint Diversity is about understanding that all people have unique experiences and see things differently. It’s not about empathy. It’s not about tolerance. And it’s certainly not about consensus.

Put simply, viewpoint diversity is about understanding and engaging in something I call “positive intellectual inquiry” to develop a better sense of self-awareness and awareness of others. There are three main objectives of practicing positive intellectual inquiry:

1. To increase awareness of self and of others.

Being more self-aware is an essential part of positive psychology. In addition to knowing our strengths, we should also be aware of our biases. We can keep in mind that we always have more to learn, and it’s important to stay curious. This helps us better understand ourselves and other people.

2. To cultivate intellectual humility.

Fostering viewpoint diversity helps to promote a culture of intellectual humility. Intellectual humility is a nonpartisan virtue. It is a check against self-righteousness and a balance that enables us to allow for ambiguity.

None of us have a worldview that is complete and we can all learn from other people. It behooves us to open up instead of shutting down and to expand our minds instead of contracting them. We can build on our self-awareness and be more aware of others simply by admitting that we don’t know everything. We might, in fact, be wrong.

3. To develop actively open-minded thinking skills.

It isn’t comfortable or easy, but we can and should actively seek out “other-side” arguments. We can challenge ourselves before we challenge others and we can seek to understand. We can ask ourselves if there is something we can agree on to move the discussion forward on a path toward understanding. Embracing open-minded thinking skills helps everyone grow and it’s something that can be integrated into all of our lives right now.

Viewpoint diversity benefits everyone. It gives us room to wonder. It’s what makes life so much less boring — that we can gaze at the same scene and see something totally different. It’s an amazing thing to experience.

We need to resist conflating identity with ideology and to recognize that other people may see and experience the same thing completely differently. As David McCullough, Jr. said to his students, “Climb the mountain to see the world, not so the world can see you.” That’s a good perspective to have. Remember that your view, magnificent and well-earned as it may be, is just one way of seeing.

That’s appreciation of viewpoint diversity and it can positively change our lives and the world around us.

Just remember—if you believe that other people matter, then their views must matter too.

One Way to Think about a Life Well-Lived

What makes a life well-lived? If I could answer that question in a blog post, I’d be pretty impressive. Alas, I am not that impressive—yet I have been impressed by the literature and philosophies that try to get to the root of this question, and by the science that can help inform us more about some things we already know. For instance, we already know well-being matters and that certain elements are associated with the concept of well-being. Leaving health and vitality aside for a moment, when we consider psychological well-being, we can look at the concept of PERMA.

Dr. Martin Seligman defined a model of well-being comprised of five elements that form the acronym PERMA—positive emotions, engagement, relationships, meaning, and achievement. While none of these elements fully defines well-being, each of them contributes to it. Having a better understanding of this theoretical model might help us maximize our own well-being, and science has shown some effective ways we can practically increase our PERMA in life:

Positive emotion—we know it’s a good thing to feel positive emotions like joy, happiness, wonder, and awe, but it’s also true that we each have a baseline in terms of how positive we can be. Still, there are ways we can focus our attention to make ourselves more positive people. One way to increase positive emotion is by writing down three things that went well at the end of each day. Read more.

Engagement is the feeling you have when you lose track of time because you are so absorbed in a task you enjoy. You’re expending effort, but it’s an effort aligned with your strengths. The way to increase engagement is to learn your strengths and apply them to your work. There are many tests you can take to learn about strengths, including the VIA Character Survey.

Relationships make an enormous impact on our well-being, so efforts to improve our communication with other people in our lives matter quite a bit. One of the best ways to improve relationships is by capitalizing on the good things—something that many people tend to overlook. This video on Active Constructive Response can show you how to celebrate good news in a way that builds better relationships.

Meaning is the need to make sense of life outside of ourselves. Seligman calls the self “an impoverished site for meaning.” It is essential to our well-being that we have some sort of purpose in life. Nietzsche said if we "have our own why in life, we shall get along with almost any how." It is important to often recall the greater impact of our work. Read more.

Achievement is something our culture tends to celebrate—but a sense of accomplishment can come in many forms, and it helps to try to work on a sense of mastery and competence. We need to build intrinsic motivation and one of the best ways to do that is by setting goals. Learn more about SMART goals.

Obviously, PERMA isn’t the only way to think about a life well-lived, but it is one way that can serve as an effective model to assess your own well-being. And the truth is that we can all be a little bit better today than we were yesterday. Why wait for tomorrow?